Yellowstone in Spring: Wildlife, Birds, and Quiet Moments

Going to Yellowstone National Park in Spring had been on my bucket list for a long time. This year, looking back, that list started to feel different.

Over the last couple of weeks, after losing my brother and watching other people I know deal with serious health issues, I found myself thinking more about life in general. About time. About what we say we want to do someday, and whether someday ever really comes. That is when I started revisiting my bucket list.

In 2023, before all of that, we finally made it to Yellowstone. We decided to go in early May, just as the park was beginning to reopen after a long winter. The crowds had not arrived yet, snow still lingered at higher elevations, and the landscape felt quiet and raw. It felt like the right way to experience a place like this. We spent 14 full days in Yellowstone, moving slowly and letting each day unfold on its own.

First Impressions of Yellowstone

Yellowstone is not just another national park. It was the first national park in the United States and the first national park in the world. On March 1, 1872, President Ulysses S. Grant signed the Yellowstone National Park Protection Act into law, and the idea of preserving land on this scale was born.

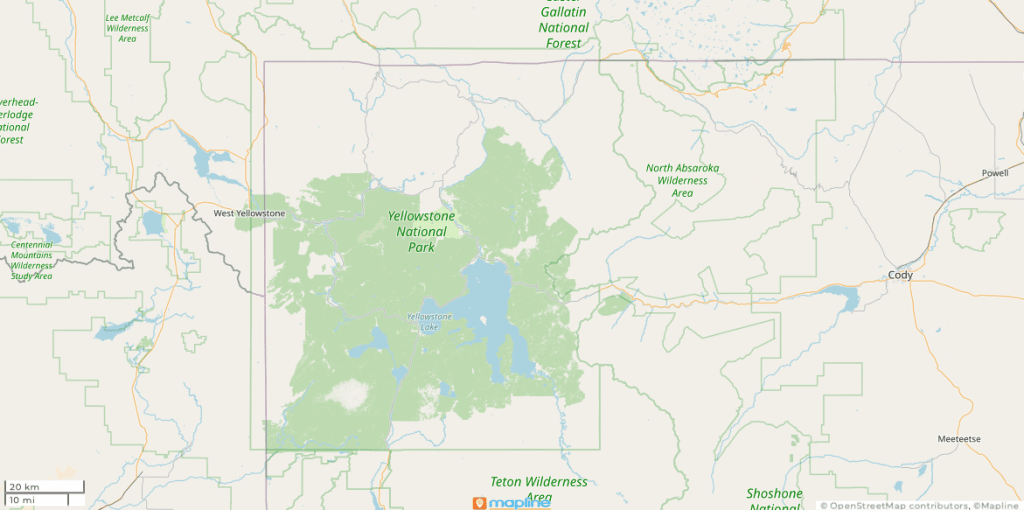

The park is vast. It covers approximately 3,472 square miles and stretches 63 air miles from north to south and 54 air miles east to west. Most of it lies in Wyoming, with smaller portions in Montana and Idaho. It is larger than the states of Rhode Island and Delaware combined.

What makes Yellowstone even more remarkable is its diversity. There are 67 species of mammals, including two species of bear. Around 330 species of birds have been recorded, with roughly 150 nesting in the park. There are 60 species of fish, six species of reptiles, and several threatened species, including the Canada lynx and the grizzly bear.

Entering the Park and Slowing Down

We flew into Bozeman, Montana, and entered the park through the northern entrance. Our trip lasted two full weeks. We stayed a few nights outside the park, but most of our time was spent inside Yellowstone.

Staying within the park allowed us to slow down, avoid long drives at the beginning and end of each day, and really settle into the rhythm of the place.

We did not hire a guide. That was a conscious decision. We wanted to move at our own pace. If weather changed, if light looked better in one area, or if wildlife activity pulled us in a different direction, we could follow it. We packed lunches, stayed flexible, and let each day unfold naturally.

A Landscape That Pulls You In

Yellowstone immediately takes you out of your element. The roads are winding and slow. Mountains rise in the distance. Rivers cut through valleys. Forests, grasslands, and geothermal areas exist side by side.

Places like Lamar Valley, Hayden Valley, and Mammoth each feel distinct, yet connected. You are constantly shifting from high elevations to valley floors, from open landscapes to dense forest. There is always something happening if you are willing to observe.

Coming from New York City, this kind of space feels almost unreal.

Geysers and Water That Never Sit Still

When most people think of Yellowstone, they think of geysers. Old Faithful is the one everyone knows, but there is so much more to Yellowstone’s geothermal landscape than that single eruption.

At one point, studies showed that more than 1,200 geysers have erupted in Yellowstone, with roughly 465 considered active in an average year. What struck me most was not just the number, but how different each one felt. No two geysers were the same. Each had its own character, its own colors, and its own setting within the landscape.

Places like Mammoth Hot Springs, Norris Geyser Basin, and Fountain Paint Pot were all completely unique. Mammoth Hot Springs, with its layered terraces and flowing mineral-rich water, felt almost otherworldly. Some pools were bright blue, others carried soft shades of pink and orange. Steam rose constantly, and the smell of sulfur hung in the air, reminding you how alive the ground beneath your feet really is.

It is incredibly important to stay on the boardwalks in these areas. The geothermal ground can be fragile and dangerous, and the park has built these paths for a reason.

These geothermal areas also created unexpected wildlife moments. Visiting in May, when much of the park was still cold, the warmth around the hot springs attracted certain species. At Mammoth Hot Springs, we watched Violet Green Swallows flying and feeding around the steam and terraces.

Water in Yellowstone does not stop with geysers. The park is home to approximately 350 waterfalls over 15 feet tall. Seeing places like UpperFalls, Artist Point, Gibbon Falls, and others throughout the park was breathtaking.

Between the geysers, hot springs, rivers, and waterfalls, water is always present in Yellowstone. It shapes the land, supports wildlife, and constantly reminds you that this place is still very much in motion.

Respecting Wildlife in a Wild Place

In early May, some trails were closed due to snow, wet conditions, or wildlife activity. Bears were coming out of hibernation, and if there was a carcass near a trail, it was closed for good reason. When we did hike, it was incredibly quiet. No cell service. No crowds. Sometimes nobody around for miles. We wore bells, talked as we walked, and carried bear spray.

Another moment from that hike still feels very vivid to me we rounded a corner and saw American bison climbing out of a river below us.

We were walking along a trail that sat slightly elevated above a lower path that led right down to the river. It was quiet, and we were moving slowly, just taking everything in. Then we heard it. Snorting. Heavy breathing. The sound of movement and water being pushed aside.

We stopped and looked down toward the river just as a group of American bison came charging out of the water. They climbed up onto dry land and shook themselves off, sending water flying in every direction. The sound alone was powerful. We had distance. We had elevation. We were safe. But we also had a front row seat to something completely raw and unscripted.

Mammals of Yellowstone

Seeing mammals in Yellowstone was just as powerful as the birding. Over the course of our trip, we saw 26 different species of mammals, many of them for the first time in the wild. Being away from the city and immersed in a place like Yellowstone gives you a completely different perspective. You are not just observing wildlife. You are moving through their world.

Of course, there were the iconic species. American bison were everywhere, often not as single animals but as entire herds. Seeing that many animals together, moving across the landscape, was something I will never forget. We also saw elk, white-tailed deer, pronghorn, bighorn sheep, and mountain goats. Seeing these animals in groups rather than in isolation made everything feel more alive and connected.

Some of the most intense moments involved predators. We saw both black bears and grizzly bears during the trip. One unforgettable sight was a grizzly bear with two cubs, viewed safely from a distance as people lined the road below a hillside. Another time, we witnessed a grizzly feeding on a bison carcass, again from a safe and respectful distance. Moments like that remind you very quickly why distance and awareness matter so much in Yellowstone

We also encountered coyotes, red foxes, and even a gray wolf. Those sightings were brief, but incredibly exciting. Seeing animals like that move through open space, completely at ease in their environment, is something that stays with you.

The smaller mammals added just as much character to the experience. Muskrats, beavers, river otters, snowshoe hares, mountain cottontails, and a variety of ground squirrels were scattered throughout the park. Golden-mantled ground squirrels, Uinta ground squirrels, and yellow-bellied marmots were especially fun to watch. Some barely moved at all, while others were constantly darting from place to place. The least chipmunks were lightning fast, making them some of the hardest animals to photograph.

Photographing mammals can be challenging. They are often less predictable than birds and far less cooperative. But even when photos were difficult, just watching behavior was enough. Seeing herds form, young animals stay close to adults, and predators move through the landscape felt like a privilege.

Overall, the diversity of mammals in Yellowstone was overwhelming in the best possible way. Being able to witness so many species, in such a vast and wild setting, was something I felt deeply grateful for. It was another reminder of just how special this place really is.

Birds Where You Least Expect Them

We were told early on that May was the wrong time to see birds in Yellowstone. Spring migration had not fully begun, and snow was still present in many areas.

That turned out not to be true at all.

Over the course of our time in the park, we saw around 70 species of birds, including 17 lifebirds. For someone who spends a lot of time birding in New York City, that felt especially meaningful.

Some species were familiar, like Red-tailed Hawks and Bald Eagles, but seeing them here felt completely different.

One moment in particular has stayed with me from those early days in the park.

We had pulled over to photograph a group of American bison, including a calf near the road. As I was focused on photographing these quiet moments with the bison and calf, I was suddenly pulled out of it by a familiar sound overhead. It stopped me immediately. That sound was familiar. A sound I knew well from birding in New York City.

A Red-tailed Hawk.

I looked up just in time to see the hawk circling, calling loudly. Then everything escalated quickly. The Red-tailed Hawk dove, pulling up sharply, then dove again. Only then did I notice what it was reacting to.

Two Bald Eagles were flying nearby.

The Red-tailed Hawk began actively dive-bombing them, chasing and harassing both eagles in midair. It was fast, loud, and completely unexpected. I hadn’t even put my camera on a tripod yet, which turned out to be a gift. I had the freedom to move, track the action, and keep shooting while others nearby struggled to reposition their gear.

What started as a stop to photograph a bison calf turned into one of the most dramatic bird encounters of the trip. Seeing a Red-tailed Hawk fearlessly taking on not one, but two Bald Eagles was incredible. It was a reminder of just how bold and territorial these hawks are, no matter where you encounter them.

And it felt strangely familiar. The same instinct, the same call I hear in Central Park, now echoing across the open landscape of Yellowstone.

Harlequin Ducks, Community, and the Reward of Asking

One thing I have learned from birding in New York is that whenever you are out looking for birds or wildlife and you come across other birders or photographers, it is always worth striking up a conversation. People love to share what they have seen. That is exactly what happened here.

We were talking with a small group of people, sharing what we had seen so far and hoping to hear about what they had come across. Someone casually mentioned that they had seen Harlequin Ducks. In the past, I had only ever seen one, maybe two, and never very close. Usually they were quiet, resting or swimming, with very little action. Then they said something that immediately caught my attention. They had seen a whole group of them, and they were actively feeding.

I asked if they would mind sharing where they had seen them. They gave us directions to a stretch of rapids along the river and mentioned what time of day they had been there. We decided to go the next day.

The spot was along a bend in the road with a small parking area that held maybe eight to ten cars. We pulled in, gathered our gear, and started down the trail.

In early May, some of the trails were soggy and muddy, so having the right shoes mattered. We took our time. The trail was not long, but you could not see the end when you first stepped onto it. As we walked, we began to hear it. A loud, steady roar. The sound of rushing water from the rapids ahead.

With every step, the sound grew louder, and the excitement built. As we reached the water, the trail continued along the rapids. There was a boardwalk, a few stairs, and spots where people could set up tripods. We noticed a couple of photographers already there, cameras trained on the river.

Then we looked out. It was incredible.

There were dozens of Harlequin Ducks. Males and females, paired up, diving under the water and popping back up again. Some were actively feeding in the rapids. Others rested on boulders in the middle of the rushing water or along the edges.

Everyone was respectful. Minimal movement. Quiet voices. Letting the birds come closer on their own terms. I had my 600mm lens with an extender, and I was thrilled just to watch them, let alone photograph them. As the morning went on, there was a real sense of shared excitement and community.

Then I noticed movement closer to the shoreline. An American Dipper. A lifebird for me.

Harlequin Ducks working the rapids and an American Dipper diving into the water and reappearing moments later.

We could hear warblers calling from the trees above.

I came away with photographs, video, and something I value just as much. I got to watch behavior. Feeding. Resting. Interaction.

We went back two more times. Each time, we stayed respectful. We stayed on the trail and let the birds lead the experience.

Every visit, the Harlequin Ducks were there, feeding in the rapids, resting on the rocks, sharing the space with the American Dipper.

The roar of the river, the changing light, and the shared experience made every visit feel different.

Nights, Stars, and Silence

At night, the park becomes something else entirely. The stars were overwhelming. There is a stillness that feels ancient.

It also gets very dark. Dark in a way that you do not experience in the city. We were glad we had brought a bright flashlight, because using a phone for light just did not work. The darkness felt thick, almost physical, and your eyes never really adjust the way you expect them to.

It was incredible and unsettling at the same time. You stand there looking up at the stars, completely in awe, but around you is nothing but darkness. You hear movement. You hear sounds you cannot immediately place. Wind through trees. Footsteps in brush. Calls in the distance.

It was awesome to experience, but also a little scary. That mix of wonder and unease stayed with me. A reminder that this place belongs to the wildlife first, and that being there means accepting both the beauty and the unknown.

Beyond Yellowstone

We also traveled south into Grand Teton National Park, which was established in 1929. We had heard that if you wanted to see moose, this was the place to go. And oh boy, did we see moose.

Seeing moose was a highlight, but nothing prepared us for the dramatic mountain landscapes paired with crystal clear water.

The Tetons rise sharply from the valley floor, and everywhere you look there is reflection, light, and space.

We continued to see birds here as well, including a Northern Harrier. Watching it hunt low over the open landscape was incredible and felt strangely familiar.

The park is located in northwestern Wyoming and covers approximately 310,000 acres, or about 485 square miles.

Grand Teton itself rises to 13,775 feet, making it the highest peak in the Teton Range and the second highest peak in the state of Wyoming.

Standing in the valley and looking up, the scale of the place really sinks in.

Bringing Yellowstone Home

Some of the photographs from this trip have become framed prints and pillows in my collection. Hopefully more to come!

This trip cleared a huge item off my bucket list. More than that, it changed how I think about what belongs on that list in the first place.

Where should we go next? I hope to see you out birding somewhere along the way.

Click here to read our Privacy Policy